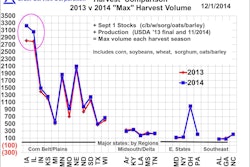

Over the past few months, agricultural news outlets have been abuzz with talk of record grain production in the Midwest. At the same time, rail competition and other transportation issues continue to plague the industry. With a large crop on its way in from the fields, farmers, elevator managers and merchandisers may be fearful that bottlenecks will slow the flow of grain and cause harvest delays and field losses.

What is a company to do when it becomes clear, at least to them, that the party to whom they have contracted grain will likely not be able to perform? Fortunately, parties faced with uncertainty need not wait for the inevitable breach to occur. The Uniform Commercial Code (UCC) provides a tool for situations where circumstances give rise to uncertainty as to a party’s expectation of the other party’s performance. The tool serves to ease the uncertainty by requiring additional assurance or enabling the demanding party to treat the contract as breached and allowing it to seek alternatives.

UCC 2-609 provides that “[a] contract for sale imposes an obligation on each party that the other’s expectation of receiving due performance will not be impaired. When reasonable grounds for insecurity arise with respect to the performance of either party the other may in writing demand adequate assurance of due performance and until he receives such assurance may if commercially reasonable suspend any performance for which he has not already received the agreed return.”

After receipt of a justified demand, a party’s failure to provide assurance of due performance within a reasonable time is a repudiation of the contract (“repudiation” is, in short, a renouncement of the contract by one party, which discharges the other party’s obligations and entitles them to damages).

UCC 2-609 provides an insecure party with key benefits upon the occurrence of insecurity. Under the right circumstances, it allows an insecure party to suspend its own performance until the uncertainty is resolved, and if it isn’t resolved, the result is a repudiation of the contract, allowing the insecure party to market the grain elsewhere in order to limit its losses. Once a repudiation has occurred, the aggrieved party may, under UCC 2-610:

- Await or agree to extend performance by the repudiating party.

- Resort to any remedy for breach, such as withholding delivery, reselling the goods, cancel the contract and seek damages for nonacceptance

- Take other steps in the exercise of reasonable commercial judgment to avoid loss.

In the right circumstances, therefore, a demand for adequate assurances can provide a party with a means of resolving an apparent insecurity before performance is due, instead of simply waiting for a counterparty to breach. Parties wishing to employ a demand for adequate assurance under UCC 2-209 should be cautious to ensure that (1) they actually have “reasonable grounds for insecurity” and (2) the assurances requested are reasonable. Each concept will be discussed individually below.

Reasonable grounds for insecurity

不幸的是,没有最高法院规则再保险solving whether a party demanding adequate assurances has “reasonable grounds for insecurity.” It is difficult for attorneys to give advice on this topic that will apply in every situation. What constitutes “reasonable grounds” will be defined by commercial rather than legal stand-ards. Whether a party has reasonable grounds for insecurity depends upon many factors including the seller’s exact words or actions, the course of dealing or performance between the particular parties, and the nature of the industry. Reasonable grounds for insecurity in one case might be insufficient in another. Examples of grounds for insecurity may include a buyer falling behind in his account with the seller, failing to live up to a separate agreement, or communicating an unwillingness or prospective inability to perform.

The grounds for insecurity don’t necessarily need to arise from circumstances directly related to the parties or the contract itself. Where the market price of a commodity is rising, for example, a buyer may be justified in seeking assurances of performance from the seller even though the seller did nothing to cause buyer’s insecurity. The 2012 drought was a prime example of a widespread concern giving parties the right to demand adequate assurance of performance.

Court rulings provide further insight into how industrywide situations can give rise to insecurity. In Top of Iowa Coop. v. Sime Farms, Inc., 608 N.W.2d 454 (Iowa 2000), a buyer of corn demanded adequate assurances from a seller based on market conditions and negative publicity in the industry. The court ruled that general concerns could support a jury finding that the buyer had reasonable grounds for insecurity. Other courts have held that “a ground for insecurity need not arise from or be directly related to the contract in question,” and that “outside circumstances may be sufficient.” Brisbin v. Superior Valve Co., 398 F.3d 279 (3d Cir. 2005); By-Lo Oil Co. v. ParTech, Inc., 11 Fed. Appx. 538 (6th Cir. 2001).

Demand for (reasonable) adequate assurance

Ok, so you have reasonable grounds to be insecure about your counterparty’s performance. What next? The official comments to the UCC describe an insecure party’s rights as “the right to require adequate assurance that the other party’s performance will be duly forthcoming.” So how does a party communicate the requirement? Courts have held that section 2-609 requires a “clear demand so that all parties are aware that, absent assurances, the demanding party will withhold performance. An ambiguous communication is not sufficient.” Alaska Pac. Trading Co. v. Eagon Forest Prods., 85 Wn. App. 354, 363 (Wash. Ct. App. 1997).

Examples of adequate assurance requested by parties may include the following, under the right

circumstances:

- Seeking a down payment or a letter of credit from a potentially insolvent buyer before sending the next shipment.

- Requesting additional sampling or inspection certificates when concerns arise as to grain quality.

- Requesting additional planning or notice to confront extended wait times, or rail delay problems.

In determining the appropriateness of the demand, courts have asked: “What are the minimum kinds of promises or acts on the part of the promisor that would satisfy a reasonable person in the position of the promisee that the expectation of receiving due performance will be fulfilled?” In this context “adequate” means minimum, because the promisee is not entitled to more security than is necessary to guarantee performance. Hawkland Uniform Commercial Code Series § 2A-401:4 (2014).

Courts and commentators have recognized that all demands for adequate assurance call for more than was originally promised under the contract, and that is precisely what UCC 2-609 authorizes. Top of Iowa Coop. 608 N.W.2d at 470 (citing White & Summers § 6-2, at 288. 454 (Iowa 2000). Therefore, an insecure promisee can demand assurance in the nature of additional performances not required by the underlying contract, provided there are reasonable grounds for insecurity. R.J. Robertson Jr., The Right to Demand Adequate Assurance of Due Performance, 38 Drake L. Rev. 305, 322 (1988-89). Be careful not to demand too much, however, as excessive demands may be deemed to be repudiation by the demanding party.

Default and/or demands for adequate assurances under the NGFA rules

Many grain and feed ingredient contracts are governed by National Grain and Feed Association Trade Rules. With respect to a default (including repudiation) by a seller, NGFA Grain Trade Rule 28 imposes on both buyers and sellers the duty to notify each other of their inability to complete a contract within the contract specifications. Upon receipt of such notification, the non-defaulting party must immediately elect its remedy.

If the defaulting party fails to notify the other party of its inability to complete the contract, the defaulting party’s liability continues until the nondefaulting party can determine whether a default or repudiation has occurred. Buyers and sellers each have their own respective versions of this rule:

“If the buyer fails to notify the seller of his inability to complete his contract, as provided above, the liability of the buyer shall continue until the seller, by the exercise of due diligence, can determine whether the buyer has defaulted. In such case it shall then be the duty of the seller, after giving notice to the buyer to complete the contract, at once to:

- agree with the buyer upon an extension of the contract; or

- sell out for the account of the buyer, using due diligence, the defaulted portion of the contract; or

- cancel the defaulted portion of the contract at fair market value based on the close of the market the next business day.”

“The exercise of due diligence” identified in NGFA Grain Trade Rule 28 includes, for example, demanding adequate assurances from the party from whom performance is due, following the establishment of reasonable grounds for insecurity as set forth above. Thus, the NGFA rules dovetail with the UCC and incorporate the concept of a demand for adequate assurance of performance.

Conclusion

The right to demand adequate assurances, if employed appropriately, can provide significant advantages, including allowing the party to make alternative arrangements and limit exposure to a potential breach and protracted litigation. With careful consideration of the appropriate steps, parties can evade a potential disaster and seek a substitute arrangement, rather than simply waiting for the inevitable breach to occur.