Grain quality is a broad term, one that means many different things given the context of the evaluation. Regardless of whether you’re looking at the physical attributes of the kernels or monitoring moisture levels, the ultimate goal is the same: money. Once the level of quality has been determined — and hopefully maintained — using grain traceability as a jumping-off point for other process improvements will allow elevators to maximize returns from both a market and a management perspective.

In the United States, grain handlers were introduced to federally imposed grain traceability systems, the tracking of the flow of grain and grain product attributes in the supply chain, as mandated by the FDA in Section 305 and 306 of the Bioterrorism Act of 2002. While Section 305 prompts elevators to register, Section 306 requires registered locations to maintain records, which identify the immediate previous sources and the immediate subsequent recipients of the grain.

“Traceability is a foundational risk management activity,” explains Dr. Tim Herrman, professor and director, Office of the Texas State Chemist, Texas A&M System. “From a regulatory perspective, if you’re going to engage in a recall, you need to be able to trace product one step forward, one step back. Once you look forward to access and manage risk in distribution and draw conclusions, then you’ll likely want to go back from what you’ve identified to the point of contamination and to identify the source.”

In recent years, the government’s regulatory focus has again been drawn toward food tracking and safety — specifically Senate Bill 510, the FDA Food Safety Modernization Act. The committee has recommended the bill be considered by the full Senate.

Under the Bioterrorism Act’s definition of traceability, handlers are not required to track intake down to the field level, and should the FDA visit a premises registered under Section 305, it would not be able to access the records a company keeps in compliance under Section 306 without cause. Once in the elevator, the preservation identity of the grain has not been mandated up to this point. As it stands, Senate Bill 510 could change this.

“Some of the wording is a bit onerous,” says Randy Gordon, vice president, communications and government relations, National Grain and Feed Association (NGFA).

The grain handling industry’s fear is that the bill would not only bring added cost to the agricultural system, but may seriously disrupt the commingled raw commodity handling, shipping and storage system. Most notably, the bill may impose stringent traceability requirements, basically identity preservation in storage and record keeping, with the goal of tracking individual shipments back to individual farms or at least a reasonable number of possible sources.

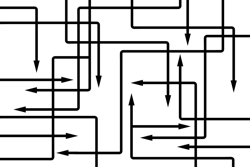

As is the nature of bulk materials, grain moves through the system as a series of “small sublots” with little identity. Once in the system, it is constantly commingled into larger and larger lots. Making it to the level of traceability proposed by the bill would be a difficult — and potentially costly — endeavor. Ag organizations, like the NGFA, are pushing amendments to the bill, hoping to preserve the economic cost-benefit model currently fueling the grain handling system.

“Senate Bill 510 is an aspiration goal set by Congress that I believe the industry will eventually be able to achieve, but we’re not there yet,” Herrman says. “Yes, at some point we’ll be able to trace grain from any point in the market system to the field(s) of origin — in real time — but I don’t know that it’s realistic within the time frame that is proposed by the Senate bill.”

No doubt the grain industry will push back on wide-sweeping umbrella regulation; however, one should consider that it may only be a matter of time before a major end user requests a level of tracking similar to what has been required in other industries.

“All it’s going to take is some hassle over toxins or something like that and then the buyer companies will start to get pushier — and the industry will have to get equally resistant,” Dr. Charles R. Hurburgh, professor, agricultural and Biosystems Engineering, Iowa State University, predicts. “All it takes is for an incident to occur with a product that is close to the consumer.”

除了潜在的成本和安全问题,博士f·William Ravlin, associate director, OARDC, Ohio State University, offers this explanation for resistance: “Nobody wants to be defined as a bad actor. You can imagine the situation where it would be beneficial to very precisely identify the chain of custody and mitigate the problems, but at the same time, you’ll get a fair amount of resistance from different parts of the industry for obvious reasons.”

If the basic traceability systems are already known, how can elevators proactively adjust their grain management processes — what internal improvements can be made — to allow an organization to easily adapt to new or unforeseen government regulations?

A team of researchers has been asking themselves the same question, and they offer a solution.

Beneficial record keeping

Working with the USDA, extension programs, university system, grain firms and private industry, a research team has been working on developing systems to address grain quality by observing quality management systems in action — and one of the most important aspects, traceability with bulk materials. They have determined that grain traceability (at any level) runs parallel with the implementation of Quality Management Systems (QMS) in effectively tracking grain once inside a handling facility.

“We found that if an elevator has grain quality problems — say grain going out of condition — it resorts to turning the grain, maybe blending it, maybe attempting to cool it, maybe putting it into another bin,” Hurburgh says. “Oftentimes there is no record of this action. Guess what that does for tracking? It blows the show, and this costs money.”

At this point, the only possible way to determine where a problem may have occurred is through the process of elimination.

“We came to realize, in grain, the best we could do is narrow the fence to some part of the list of local producers feeding grain into the elevator,” Hurburgh says. However, he notes, if the FDA were to request a specific list of producers — say for a recall or bioterrorism — handing over a stack of records and explaining, “Here’s a list of my customers for the last two years, it could be anyone of those” isn’t going to cut it.

The solution, as Hurburgh admits, is rather obvious: “If you just write down: what bin you took grain out of, when, how much, and where it went; and integrate that with your database, you can then identify and eliminate candidate bins if there is a problem.”

While an elevator will never get a 1:1 correspondence of bulk products, of what comes in and exactly where it goes on the outbound side, if a series of recording processes are put in place — basic record keeping — it can limit the universe of possibilities down to about 70% accuracy.

“By doing forensic exercises — mock recalls — we could make steady improvement in the number of possibilities for any given problem by cutting down the possibilities,” Hurburgh says. “Here it is, now this sounds basic and simple, but just record what bin the grain went into the first time it showed up. If you don’t do that, you’ve completely lost it in the system.”

Traceability in action

“Traceability is a synonym for inventory control,” Hurburgh says regarding the strong connection between rigid quality management system practices and the efficiency of inventory management. “And if you look at it that way, traceability is simply a business management process.”

The benefit: If you know which bin the grain went into, if you know what was transferred in and out, and it was graded carefully when it was transferred, you can keep the quality records of the elevator much more realistic than a simple guess, and your inventory is much more accurate.

Similar to other formalized, statistically based quality management systems, like ISO-based standards, traceability came as a subset of the need for formalized record keeping in the grain and grain processing industries. While other raw materials require a very exhaustive analysis of products as they go in and out of the system, in a grain elevator, they typically do not.

“你亏钱,如果你不知道为什么re your grain is,” Hurburgh explains. “You lose money on the blend. You’re potentially losing money because bad quality starts to build up and you wonder why… There are a number of ways you can lose money if you don’t know; and ways that you could make money if you do know.”

Put simply, the primary incentive for imposing quality management systems: It’s good business and effective management.

“未来跟踪技术将使粮食我ndustry to trace grain back to the field level,” Herrman explains. “You may be able to identify the source of grain to individual farms or fields. It would be a composite, but would be providing more detail than current record-keeping systems.”

Added benefits of a QMS

“I find it is characteristic, in any industry, that we tend to be data rich and information poor,” Herrman says.

While it may be customary to collect more records than are utilized, capturing the value of those records is a function of management — and what you do with this paperwork could hold the key to greater, less obvious, returns.

“As an industry we have to focus in on the cost-benefit aspects of quality management systems with traceability, not the regulatory aspects,” Ravlin says.

“Once you start paying closer attention to your record keeping, you find there are ways to improve process efficiency,” Dr. Dirk Maier, chair of the Department of Grain Science and Industry, Kansas State University, explains. “It’s not so much about traceability, which is for food safety; it’s about taking a quality management approach. By taking a process approach, you improve the efficiency of operations and ensure quality at each point — and in everything you do in a quality manner.”

According to Hurburgh, QMS and traceability can be a source of profit — not a source of cost — if it’s approached in the proper way: “If a company does just enough to comply, saying, ‘What’s the minimum I have to do to get the inspector off my back?’ — if that’s the attitude, it’ll be a cost. You’ll have a stack of paper and not get anything out of it. However, if you approach it positively, ‘This is a process of evaluating and restructuring my operations to be more efficient in today’s economy’ — then it will be a benefit and not a cost.”

In the long run, business will take over in terms of spreading the notion that perhaps operations need to be managed a little more industrially, Hurburgh says: “The concept of quality management and input/output tracking is not new; it’s just new to agriculture.”

Tradition aside, the bottom line economics speak for themselves. The added bonus, Hurburgh says, QMS and open lines of communication change the culture of an organization by reducing insurance costs, improving employee training and lowing turnover.

“You get collateral benefits along the way as you tighten up business practices,” he says. “Oh, and you now have a system that makes it easy to comply with bioterror regulations, documentation for workers, safety programs, security — all these process-based regulatory programs can be swept into quality management systems. The compliance becomes much cheaper than doing each step independently one at a time.”

QMS credentialing

Trade organizations are taking notice of the need for QMS training and continuing education. GEAPS, specifically, has been exploring the development of a distance education program — and even taking it another step by discussing credentialing through Kansas State.

Hurburgh predicts: “Whether it’s certification or credentialing, there’s a certain formality to it. Continuing education keeps employees aware of new developments and technology in the grain industry. I could see this taking off — really because it’s going to make companies money.”

He also feels that under this model companies will find that certified employees make better decisions, and have fewer problems overall. Perhaps the balance may lie between a level of self-imposed certification rather than one that is dictated by a regulatory agency.

“Achieving compliance through participating in voluntary programs is desirable,” Herrman says. “In the future, the grain industry will be able to provide an enhanced level of traceability without any major infrastructure alterations. I don’t think we need to sacrifice the efficiencies that exist in our U.S. grain handling and marketing system to do so.”